Devin Jefferies, a Master of Engineering student at Stellenbosch University, has presented research, under supervision of Doctors JC Schoeman and Benjamin Evans on teaching an artificial intelligence to race. His work focuses on a specific challenge: how to make an autonomous car drive at its limits on a track it has never seen before. This research also documented the agent’s performance when moved from a simulation to a physical vehicle.

The Engineering Challenge

The field of autonomous racing has been a test bed for vehicle control systems. Many systems rely on “classical control methods”. These approaches require precise maps of the racetrack to plan an optimal path in advance. They can be very consistent, but their reliance on pre-planned routes limits them to “known, static environments”. A vehicle using this method cannot easily adapt to a track it does not have a map for, or to sudden obstacles.

An alternative is deep reinforcement learning, or DRL. These algorithms learn more like a person, through a “trial-and-error process”. They do not need pre-planned trajectories. This structure should, in theory, make them better at generalising to new situations, like unseen tracks. The main drawback has been performance. DRL algorithms have typically been slower and less consistent than the classical methods.

Jefferies’ research set out to close this performance gap. The goal was to produce a DRL agent that could generalise to new tracks while also matching the high-speed performance of its classical, map-reliant counterparts.

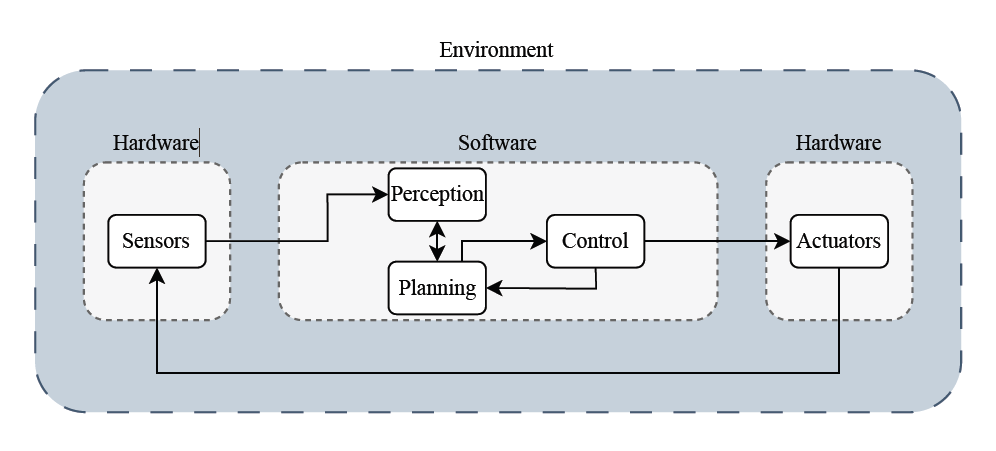

Figure 1: A possible implementation of the autonomous driving pipeline where the black arrows show the flow of information along the pipeline.

A “Centre-Orientated” Solution

The research introduces an “end-to-end racing framework”. The method is named the “centre-orientated twin delayed deep deterministic policy gradient” (CO-TD3) agent. It functions by feeding raw sensor measurements from a LiDAR (a laser-based scanner) directly into the agent’s network, which then outputs commands to control the vehicle’s speed and steering angle.

A common problem for DRL racing agents is erratic steering, described in the thesis as a “slaloming and jerking motion”. This occurs when the agent over-corrects, moving too close to one wall and then back-correcting toward the other.

- Jefferies’ research identified a way to correct this. He engineered a “centring term” and added it to the agent’s state vector (the set of information it uses to make decisions).

- This centring term is not a pre-planned map.

- Instead, it is calculated in real-time using the live LiDAR scan.

- It is computed by averaging the first three and last three distance beams of the 180-degree LiDAR scan.

- This calculation gives the agent a constant “indication of how far it is from the centre of the track” at any given moment.

This new information, combined with a “reward function” that penalised the agent for straying from the centre and rewarded it for fast, complete laps, helped stabilise the vehicle’s behavior. The research found that this addition “increased the consistency of the agent’s action selection”.

To test the agent’s ability to generalise, Jefferies also developed a “random track generator”. This tool can produce a large set of diverse and challenging new tracks, preventing the agent from simply “memorising” one or two training courses.

Performance in Simulation

The CO-TD3 agent was tested in the F1TENTH simulator against several benchmarks on four standard tracks. The agent’s performance was not just stable; it was fast.

On the “AUT” (Austria) track, the CO-TD3 agent’s fastest lap was 15.51 seconds. This time was faster than the classical “Opti. & tracking” (16.79s) and “MPCC” (16.87s) methods, which both rely on pre-planned trajectories. The agent also posted faster times than other DRL methods on all tested tracks.

The primary goal of the research, generalisation, was tested next. The CO-TD3 agent was trained on a single track (“MCO”). It was then tested on 50 new, randomly generated unseen tracks:

- CO-TD3 Agent: Achieved a 100% completion rate at a maximum speed of 8 m/s.

- Standard TD3 Agent: A baseline agent without the new centring term and reward structure only managed a 46.67% completion rate, and at a much slower 4 m/s.

The CO-TD3 agent could also successfully avoid new, randomly placed obstacles on the track, even though it was never explicitly trained to do so.

From Simulation to Reality

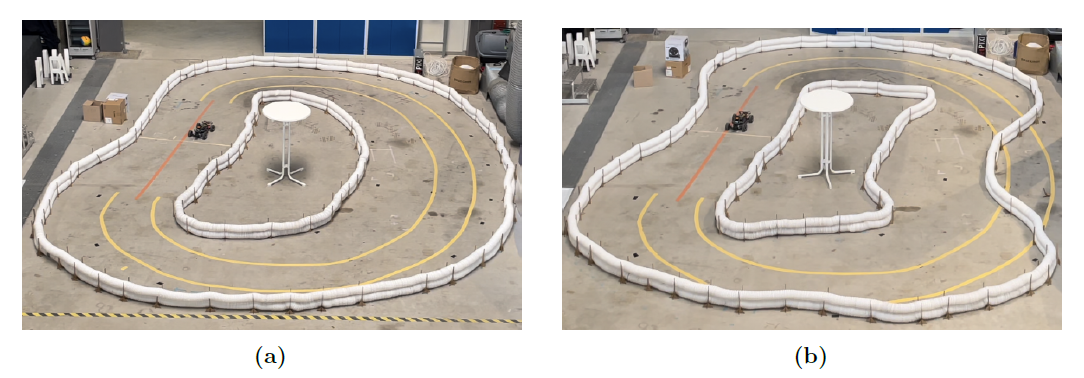

The final test involved moving the agent from the simulation to a physical F1TENTH vehicle. This step often reveals problems, as real-world sensors and motors are not as “ideal” as their simulated counterparts.

Jefferies trained an agent in simulation on a map of a physical track. He then loaded that agent’s learned weights onto the real car’s computer.

The agent, with no further training, achieved a 100% completion rate on the physical track. The performance closely matched the simulation:

- On Real Track 1: The agent’s simulated lap was 6.44 seconds. The physical vehicle’s lap was 6.45 seconds.

- On Real Track 2: The agent’s simulated lap was 6.60 seconds. The physical vehicle’s lap was 6.75 seconds.

This success was repeated for generalisation. The agent was trained on a different simulated track (“Alternate track 1”) and then placed on the physical “Real track 1”, which it had never seen. It successfully completed the lap in 6.27 seconds, demonstrating its ability to generalise to physical hardware.

Figure 2: Images of the test set-up with the real vehicle for both (a) real track 1 and (b) real track 2.

Implications and Future Work

This research shows that a well-designed DRL agent can compete with, and in some cases exceed, the performance of map-based classical algorithms. The ability to learn a general driving policy, rather than just following a plan, is the main distinction.

This work opens avenues for more dynamic problems, such as head-to-head racing, where predefined plans are insufficient . These are the types of algorithms that may one day be used in “mixed traffic urban settings,” where cars must react to new events without a script.

Download and read his full research: https://scholar.sun.ac.za/items/43e6d233-2024-46d0-9ae8-ba3029360954